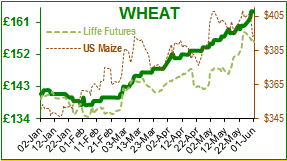

This week November wheat futures hit contract highs of £161.50/T driven in part by weakness of the € against the $ (political uncertainty in Italy and Spain). Global wheat markets have also firmed due to dryness, and the combination has driven the September Matif futures upwards by €15/T over the past two weeks before easing €5/T this week.

Then UK November futures followed, with the highest prices seen since May 2014, and is currently trading at £158.50/T. Old crop wheat is being driven by lack of availability and both bioethanol plants are continuing to erode remaining stocks, with spot price at £164/T. The May AHDB supply and demand figures indicate the tightest UK wheat market in four years. Domestic consumption is significantly higher since March, as human and industrial use and demand for animal feed have increased.

Analysts forecast that the 2018/19 EU wheat crop is similar, in terms of size, to last year’s, despite this year’s long winter. Ikar forecast the 2018/19 Russian wheat crop at between 69.5Mln T and 77.5Mln T (USDA 72Mln T) demonstrating the mixed signals being reported in many areas globally regarding crop conditions and yield. The weather continues to drive much of the volatility in cereal markets with less than ideal conditions potentially effecting yield from regions of Eastern Europe, the Black Sea, Australia and America. In Australia there are reports that up to 70% of the winter wheat crops were planted into dry soils following six months of well-below average rainfall. In the Black Sea crop reports are varied with some experts reporting a wheat crop of below 70Mln T with continued dry conditions sufficient to damage yield potential, while others forecast rains in time to replenish the deficit.

The overall concern is that while current global yields are similar to last year, expectations are that these could change dramatically. Global grain supply (wheat, maize, barley & sorghum) is estimated to decline to a three year low (see AHDB graph). With consumption up, and less carryover for most cereals into the next harvest year combined with weather issues, the markets going forward could react with more volatility than in recent years to any pressure or potential problem with an already tightened world supply and demand outlook.

The soya futures are relatively stable but subject to volatility following worry from continued trade negotiations between the US and China along with new tariffs the US president has just placed on EU, Mexico and Canada (steel and aluminium imports). Despite an earlier pledge by China to increase imports from the US, its biggest trading partner, that the US is willing to risk damaging relationships with political allies to put America first is being seen as a negative driver within World trade. The World waits to see if anyone is brave enough to retaliate. Politically the world has become more dangerous (Putin, Trump, Kim, Brexit, etc). Strikes by truckers in Brazil continue to disrupt the soya supply; so much so that two main ports reported that they ran out of soya causing a backlog of vessels. Despite most blockades being removed, there are reports that each strike day resulted in the loss of 24m Brazilian chickens with an estimated loss of $350Mln. The Argentine Ag Ministry reduced its 2017/18 soyabean crop estimate by 1 Mln T to 36.6Mln T (USDA 39Mln T).

In surprising news, the EU raided the offices of the Belgian Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain in relation to the 2017 Fipronil scandal. The NVWA, the food and product safety board of the Netherlands has already undergone a lawsuit for negligence and delays in providing information, increasing financial losses to egg producers.

In 1128, Saint Norbert of Xanten founded an Abbey in Grimbergen (Belgium) and soon afterwards started brewing beer [as in medieval times beer was safer to drink than water from streams and rivers]. The Abbey became famous for its home-brew, the recipe of which was centuries old when the abbey was dissolved in 1796 (French Revolution). The beer was so famous that in 1958 a brewery (now Carlsberg) started to market ‘Grimbergen beer’ by agreement with the monks, even though the original recipe had been lost.

The Abbey emblem is the phoenix because the abbey has survived numerous fires. The monks intend to start a micro-brewery following the original recipe. So four medieval historians have spent a year (so far) combing through 35,000 manuscripts (mainly written in medieval Dutch) looking for the formula. So far they have located the list of ingredients, but not the proportions nor the process; what, no medieval declaration ticket?